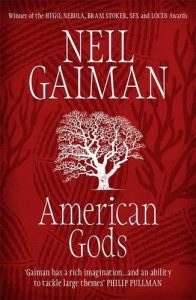

American Gods by Neil Gaiman is a multi-award winning fantasy novel that mashes up ancient and modern mythology and mixes it with mystery and some gruesome horror. I read the author’s preferred text, which expands on the original, and found it disturbing, funny, thought provoking, and hugely enjoyable. I’m going to dig into the book and explore some of the ideas I had while reading it, so expect spoilers!

American Gods by Neil Gaiman is a multi-award winning fantasy novel that mashes up ancient and modern mythology and mixes it with mystery and some gruesome horror. I read the author’s preferred text, which expands on the original, and found it disturbing, funny, thought provoking, and hugely enjoyable. I’m going to dig into the book and explore some of the ideas I had while reading it, so expect spoilers!

Like any good book, American Gods is about many things. On one level, it can be read as a story about storytelling. It’s a huge rambling novel where people and gods tell each other stories that layer up into a larger, mythical tale about the power of stories and imagination and how they shape our reality, and the dangers inherent in that process.

The story explores what it means to be American through its myths, specifically immigrant myths. Immigration stories pop up throughout the book like historical flashbacks and show how the American soul has changed over the centuries, and how the people created the country with their stories. In his essay, How Dare You?, Neil Gaiman explains the birth of the book:

“It would be a thriller, and a murder mystery, and a romance, and a road trip. It would be about the immigrant experience, about what people believed in when they came to America. And about what happened to the things that they believed. … I wanted to write about myths. I wanted to write about America as a mythic place.”

The story follows ex-con Shadow who is released from prison early because his wife has been killed in a car accident. On his way home, Shadow encounters the mysterious Mr Wednesday who offers him a job as his driver and errand boy. After discovering that his wife was unfaithful before she died, Shadow takes the job, although it’s pretty clear he’s been manipulated into it.

And so begins an hallucinogenic road trip where we meet all kinds of strange and wonderful characters, and Shadow realises that Mr Wednesday isn’t strictly human. He is, in fact, an embodiment of the ancient Norse god Odin, struggling to survive in America now that nobody believes in him anymore. To make matters worse, there are all these newfangled gods taking over – like the Technical Boy, god of computers and the internet; Media, goddess of TV; and the Black Hats: Mr World, Mr Road, Mr Town, et al. who are spies for the new gods.

Mr Wednesday and Shadow travel around America to recruit the old gods to fight in the coming battle. The old gods come from all over the world and, like Odin, are struggling to survive and have found their own ways to get the energy they need from humans. They’ve been reduced to grifters and conmen and prostitutes and funeral directors who eat tiny pieces of the bodies they dispatch into the afterlife.

There’s a clear contrast between the earthy, chthonic gods that used to give meaning and shape to people’s lives, and the arrogant new gods who come across as stereotypes and clichés. This is deliberate, not Gaiman being lazy. (Although the new gods have dated badly: Technical Boy is a fat kid in a limo with bad skin. These days he’d be more like Zuckerberg and has been updated for the TV adaptation.)

There are also forgotten gods that Shadow encounters in his dreams and visions, which provide a clue to his function in the story. He’s a shamanic character, able to travel between the world of man and the world of the gods. He’s called Shadow because he follows others – he goes where he’s told and does what he’s told. He starts out passive and almost blank, always a pawn in somebody else’s game. He doesn’t believe in anything and is an outsider in his own country, and even in his own life. Gradually he learns to think for himself and create his own meaning – his own story and beliefs.

He does this through his encounters with one particular god, possibly the most important one in the novel, who isn’t really a god: the buffalo-headed man. Buffalo is Shadow’s spirit guide or totem, and appears in his dreams to guide him on his journey. When Shadow asks what he should believe, Buffalo answers:

“Everything.”

Buffalo also provides an important connection to the oldest beliefs in America when he explains who he is:

“‘Are you a god?’ asked Shadow.

The buffalo-headed man shook his head. Shadow thought, for a moment, that the creature was amused. ‘I am the land,’ he said.”

It’s often said that America was founded by immigrants. It’s usually portrayed as a young country compared with Europe and elsewhere, but that’s only true if you ignore the history before the land was ‘discovered.’ American wasn’t founded by immigrants – it was colonised, and the colonisers brought their gods with them.

America is only a young country because it’s in denial of its history and treatment of the indigenous people of the land. Gaiman tackles this denial and tendency to rewrite history in the historical stories as told by Mr Ibis, or Thoth. According to him, the oldest god (a mammoth) arrived in 14,000 BC, carried by the shaman Atsula. The mammoth god warned his people that the land was hostile to the gods, and so it turns out.

The old gods meet up at roadside attractions because they’re the equivalent of places of power. In the story, America doesn’t have sacred places, it’s not an old enough culture, so they have to make do with things like the House on the Rock. People come to ‘worship’ at these places, but it’s a shallow kind of worship, as Mr Wednesday explains:

“…in the USA, people still get the call, or some of them, and they feel themselves being called to from the transcendent void, and they respond to it by building a model out of beer bottles of somewhere they’ve never visited… people feel themselves being pulled to places where, in other parts of the world, they would recognise that part of themselves that is truly transcendent, and buy a hot dog and walk around, feeling satisfied on a level they cannot truly describe, and profoundly dissatisfied on a level beneath that.”

The story suggests that American culture is too materialistic to sustain genuine spiritual beliefs that provide meaning and connection. The old gods aren’t rooted in the land, and the new gods are no better. They may appear powerful, but they’re superficial and their power vanishes the moment the wifi connection is lost. Modern life cuts people off from the things that sustain them and creates a dangerous void that we try to fill with distractions that the new gods happily supply.

But the new gods are soulless and a bit sad. Technical Boy can’t function without a signal, showing that his power isn’t that strong compared to the land of the Native Americans. The land is always there and doesn’t need us, unlike the gods in the story who rely on humans to sustain themselves. They need us to believe and make sacrifices to them, but the only way they can do that is to trick us. The old gods are con artists, which brings up the question of whether they’re real or imaginary. Gaiman even says at one point that this can’t be happening, it’s not real, it’s a metaphor.

Perhaps that’s the author being meta, or maybe he wants us to think about what we believe in and how we use stories. Is imagination real, or is it a con? Are we just telling ourselves stories, believing what we want to believe?

We use ideas and stories to make sense of reality, but they aren’t real in themselves until we make them real by investing them with energy through our belief. People are looking for an identity and security – for roots – and they want life to make sense, so they tell stories. But stories aren’t reality and that leaves us with an emptiness, a longing or spiritual hunger.

Into that void steps the gods, whether old or new.

The story explores how the culture and values of America have evolved, and what happens to people when they no longer have a mythic foundation in their lives – a meaningful story that places their lives into a larger context. The old gods bound people together and provided a sense of community and connection. But the new gods of media and technology are fleeting and ephemeral with no real connection. They’re isolating and atomising.

In the end, Shadow doesn’t side with either the old or the new gods, and sees through the con at the heart of the gods’ plan for war, guided by the buffalo-headed man. In other words, it’s his connection to the land, his belonging, that saves/redeems him.

Perhaps Gaiman is saying that we’re conning ourselves by turning away from the land to believe in our own bullshit stories. By embracing the new gods of technology we’ve turned our backs on something more meaningful and allowed this dangerous void to open up. If you don’t have roots, something real to belong to, and if you don’t know who you are, then you’ll believe in anything. You’ll be open to any con, and give your life over to anything, even some dodgy god with one glass eye.

It’s saying we should honour and be grateful for the real gods that feed and clothe us and keep us alive – i.e. the land, water, air, sun, and so on. We shouldn’t waste our energy on imaginary gods that just feed on us because they have no real power without us. Stories can’t exist without humans. But humans can’t exist without the land.

“People believe, thought Shadow. It’s what people do. They believe. And then they will not take responsibility for their beliefs; they conjure things, and do not trust the conjurations. People populate the darkness; with ghosts, with gods, with electrons, with tales. People imagine, and people believe: and it is that belief, that rock-solid belief, that makes things happen.”

American Gods focuses on a particular group of gods – immigrants (or colonisers, if you prefer). Gaiman ignores the gods that are doing well in America, such as Christianity, and chooses to concentrate on the ones that serve the story. Jesus turns up briefly, but isn’t referred to by name – and I can’t go into that without spoiling the best bit.

Odin dismisses the churches that are found all over America, as being as significant as “dentists’ offices.” He’s like a defensive, sulking adolescent, angry because nobody believes in him and he’s not getting his way anymore. Odin is a jealous god. This is why he wants the war and the entire story is about his manipulations to bring that about. The only way he can survive in this land that’s bad for gods is through an immense sacrifice.

This seems appropriate. After all, if you want to talk about the soul of America, then you have to talk about war and violence. Mass sacrifice was exactly what the soul of America was built from. The country was founded on genocide. The message seems to be: Belief makes things happen, so be careful what you believe in.

One thought kept popping into my head as I read this book: Do we imagine the gods? Or do the gods imagine us?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter, but in the end, the land has the final say. The buffalo-headed man gives this warning about the immigrant gods:

“They never understood that they were here – and the people who worshipped them were here – because it suits us that they are here. But we can change our minds. And perhaps we will.”

Read more on Neil Gaiman’s website

More: Fantasy Reading List

Images: TV Show

Thought I’d drop a line to tell you I found another good Gaiman story. It’s called The Goldfish Pool and Other Stories (it’s just one short story) from the collection Smoke and Mirrors.

I also watched the movie version of Ballard’s High Rise last week. I found it uninteresting. I guess there was never a chance it was going to encapsulate the psychological arc of the novel but I’d hoped some of his points about unsustainable artificial landscapes and dehumanisation might have come through. Instead it’s just a lurid, shallow critique of class, sexual politics and social climbing with the more extreme behaviour of the characters rendered pretty much inexplicable. The complexity of the main protagonist, psychiatrist Robert Laing, is lost and he’s reduced to an opportunistic sociopath. Heck, they never even drained the swimming pool. How can you have a Ballard story without a drained swimming pool?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read ‘Smoke and Mirrors’ yet – I’ll add it to my list.

Haven’t read ‘High Rise’ either, but I have seen the film. Not sure what to make of it – didn’t enjoy it much. It felt very empty – just remember shrugging at the end. I expect the book is better…

LikeLike

Hardly an original one. The Norse gods have been Americanised as comic book superheroes/supervillians at least since Marvel comics introduced Thor in the 60s. And Gaiman himself mined a similar vein pretty thoroughly in Sandman, notably with the characters of Cain and Abel (though his portrayal of Death as a teenage goth girl was more interesting).

Mythic characters arise from the depths of our collective psyches and from Homer to Zelazny they’ve been portrayed as icebergs – a lot more happening underneath than on the surface. With Gaiman OTOH its more ‘what you see is what you get’ and he uses the Hollywood technique of establishing his two dimensional cut-outs right from the outset so mass audiences will quickly feel they’re familiar and unchallenging. His ‘reveals’ are utterly predictable (e.g. the ultra-contrived nickname ‘Low Key’ to hammer home what’s going on to anyone who missed the significance of ‘Wednesday’) and serve as petty rewards to readers who think they’re insightful for seeing them coming.

Gaiman’s characters use their mythic status as cheap adornments – as with metal bands who employ the umlaut – rather than as symbols pointing towards something beyond our conscious selves.

A friend assures me that The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a cut above the usual Gaiman and I’ll probably take a crack at it soon. He’s easy to read at least, though I find him unsatisfying except as a comic book author (the Ronald McDonald of speculative fiction?).

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s possible that I’m reading more into it than is there – it’s hard to tell.

I haven’t read Sandman yet either, or The Ocean at the End of the Lane. I’ll have to add them to the list.

So many books, so little time…

LikeLike

Exactly.

How can anyone find time to write when there’s so much to read?

And why isn’t there some enterprising chemist putting Tolstoy into a pill?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha! 😀

LikeLike

I just finished The Ocean at the End of the Lane and, yeah, it’s way better than American Gods IMHO. I won’t spoil it for you beyond acknowledging that Gaiman does know how to write something mythic when he wants to, though perhaps he only learned it relatively recently.

A bit of irony was that the first acknowledgement in the end notes was to Maria Dahvana Headley. I recently read a compilation called The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories in which the strongest (and most mythic) contribution was Headley’s Black Powder. The lamest was Gaiman’s Somewhere in America, which was simply the chapter from American Gods about the taxi driving djinn. He even had the gall to put ‘(c)2017’ on it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely needs to go on the list then…

BTW, you must read insanely fast!

LikeLike

It’s a pretty short book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, one more thing I can tell without spoiling the book is that it’s pretty much YA. Written mostly from a 7 year old point of view, though the prose and subject matter is pitched more at teenagers. But one of the characters makes the excellent point that we’re all really still kids. We’re just playing at being grown up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’re going to have to agree to disagree about Gaiman in general and American Gods in particular.

I found the novel pretty trite and shallow. Far more ‘American’ than ‘Gods’. Maybe the superficiality of the new gods had a narrative purpose but the immigrant ones were also Hollywood cut-outs of the real thing. And that’s something that I found infecting the whole story. Gaiman wasn’t trying to write a novel, he was pitching for a screenplay, with all the road movie plus gratuitous violence plus heavily signaled plot twists that go with it.

Roger Zelazny was doing that sort of novel a whole lot better in the 60s and 70s as was Samuel Delany and several others. Gaiman is at his best writing comics and American Gods is what I would expect to find in a Marvel or DC superhero story with its overblown yet underdeveloped characters and action driven set pieces. Or from Gaiman’s Sandman series (which is pretty good for what it is). Fairy floss fantasy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the old gods aren’t meant to be like the originals – they’re Americanised versions of the gods that have been imagined by people – so that’s why they’re a bit crap. That’s kind of the point.

I haven’t read any Roger Zelazny yet – I think he’s on my list.

LikeLike